Traditional handmade washi paper can be found everywhere in Japan, from name cards to beautiful wrapping paper. Until now, the largest washi never exceeded 3 feet x 6 feet long. But washi as large format installation art, using paper tapestries up to 50 feet long, brings this ancient process to a new artistic and technological level altogether.

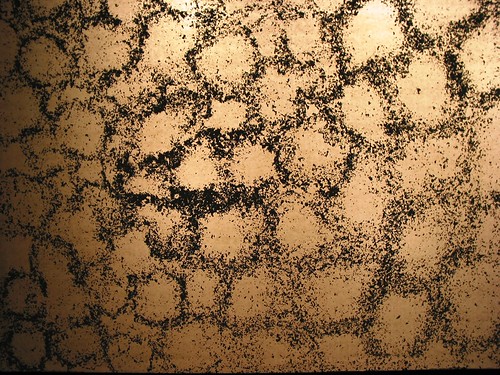

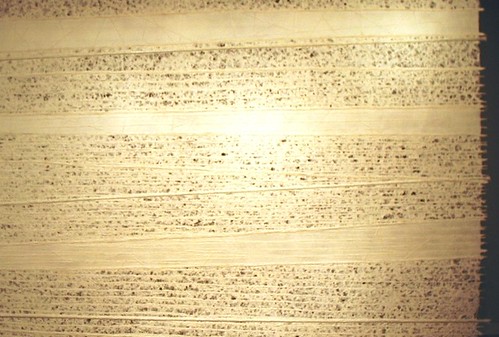

Situated in a narrow old Kyoto neighborhood is the studio and showroom of one of Japan's most successful contemporary artists, Eriko Horiki. As each distinctly different, 10 foot long sample of her washi art after another is rolled out on ceiling tracks, the paper reveals its beauty: thin fibers creating delicate swirls around tiny bits of mulberry bark, long coarse strips of bark floating dramatically in what looks like churning whirlpools. Washi's color and texture are enhanced by light, and as Horiki slowly shifts the light source from the front to the back of the piece, the fibers within the paper become illuminated and then disappear, creating an ethereal experience for the viewer.

It takes ten skilled workers to produce a piece of Horiki's large format washi -- five artists and five craftsmen in an elaborate, almost choreographed operation. Horiki explains, "Washi can be created to specifically match any architectural need or function." However, there is an additional, unknown element that always finds its way into this art. "Because the paper involves natural bark fibers floating in water, we cannot completely control the outcome of the finished work. We have come to accept nature as a part of the collaborative process."

Horiki came from neither an art nor a craft background. After working for four years in banking, she moved to the accounting department of a company that specialized in developing products made from washi. She then came into contact with professional paper artisans in the washi-making town of Imadate in Fukui Prefecture. Becoming completely captivated by the workmanship of these craftsmen, she decided to devote herself to this paper production to help ensure that washi making skills handed down over 1500 years would be passed on to the next generation. Today, you will find her works provocatively installed as walls, room dividers, ceilings and windows in restaurants, hotel lobbies, and public spaces throughout Japan, bringing drama and exceptional beauty to the surroundings.

"I was a complete amateur when I jumped into this business," Horiki confesses. "If I had had more experience, I would only have seen impossibility in the task I had chosen." But through visits to public buildings, study of their design and decoration, and sheer perseverance, her studio was born.

Public places are plagued with cigarette smoke, direct sunlight and human beings with curious fingers. Washi can tear, burn, lose color, get dirty and contract or expand, making it difficult to use as a building material. It takes as much effort to protect the washi as it does to design and create it. But Horiki likes challenges. "I have always believed that, no matter how seemingly impossible a project, if it is an idea which came from a human mind, then a human mind can come up with a solution. I must go forward and do it."

Horiki found the solutions to many potential problems through technology, sandwiching her washi in glass when necessary, and allowing the stunningly warm, soft and radiant paper to thrive in the harshest environments. But since standard glass creates distracting reflections, her team had to painstakingly innovate ways to prevent glare, all while following safety laws that obliged them to use the same shatterproof glass as in car windshields. In addition to being artists, her crew must also be scientists.

One of Horiki's most exciting projects was a collaboration with cellist Yo Yo Ma, a 46 foot long by 13 foot high single piece of washi that is the stage backdrop for his "Silk Road" concert tour, which debuted at Carnegie Hall. "Yo Yo Ma first found out about us when he saw our work here in Kyoto," Horiki explains. "We talked about the traditional and innovative aspects of washi, and new possibilities in music and stage decoration."

"The Silk Road symbolizes the connection between time and place," Horiki says, and her team worked for two months to create a set embodying the essence of the Silk Road, the ancient Asian highway which connected peoples of many cultures from east to west. For some 20 minutes during the show, the entire stage environment slowly changed as Horiki's work was illuminated through lighting techniques corresponding to the inflection of the music.

Committed to excellence, energized by challenges, talented and hard working, Eriko Horiki is an inspiring example of how traditional Japanese crafts are being reinvented as one-of-a-kind works of art for the 21st century.

Yet to a Westerner her pieces might not even look Japanese, but amazingly international. Horiki sees this, in part, as the flow of ideas enabled by our contemporary world: "People meet and are influenced by each other, people are influenced by previous eras, people from different countries influence each other. From all of this interchange comes the birth of a new culture."

http://www.huffingtonpost.com/steve-beimel/meetings-with-remarkable-_2_b_875348.html